Adventures in the History of Zero!

Zero, which literally counts nothing, is really a hero in modern life. We see it everywhere from stores, where it distinguishes between $34 and $304, to popular culture, where it is a derogatory term for someone who has nothing going for them. Because zero is all around us, we often take for granted how revolutionary the concept of zero actually was to our ancestors. So, this installment of A Grade Ahead’s history of math and science explores the amazing and adventurous ascendence of zero!

A Grade Ahead’s programs can satisfy your child’s curiosity about math and science! Take a free assessment or sign up for a free trial class at an academy near you.

Zero’s Origins as a Mere Place Holder

Zero’s Origins as a Mere Place Holder

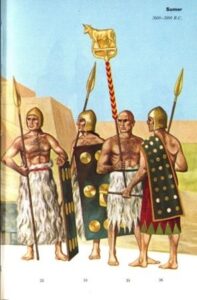

Once upon a time, around 5,000 years ago, the Sumerians in Mesopotamia needed a number system to keep track of the crops, livestock, and other resources being traded in the markets. This was nothing new of course. Many other ancient civilizations needed to count goods, and they all encountered the same issue—how do you tell the difference between 26 bushels of wheat and 206 bushels? The Sumerians, however, were the first to develop a wedge symbol to serve as a placeholder to mark the space between nonzero digits in their number system. Now, they could count 102 baskets of fish!

A Grade Ahead teaches place value as early as our first-grade curriculum. Find out more here.

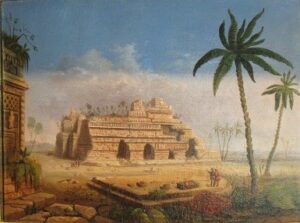

The Maya of Central America independently discovered zero’s advantages in the fourth or fifth century CE. This advanced civilization also recognized the need for a placeholder between two nonzero numbers, so they developed their own symbol. Again, though, there is no evidence that they saw it as anything but a placeholder either.

The Maya of Central America independently discovered zero’s advantages in the fourth or fifth century CE. This advanced civilization also recognized the need for a placeholder between two nonzero numbers, so they developed their own symbol. Again, though, there is no evidence that they saw it as anything but a placeholder either.

The ancient Greek mathematicians and philosophers, on the other hand, rejected the concept of zero as a number or even a placeholder, arguing that “nothing” could not even be represented by any sort of symbol. The Romans were not any kinder. They used letters rather than numerals in any case, so they also had no symbol for zero. Who counts nothing anyway? Because they did not have a sense of zero as a placeholder, most people could not distinguish between numbers like 24 and 204 without a teacher to explain the difference. Thus, math class was only for the elite in ancient Greece and Rome. It also limited their ability to fully explore the possibilities of math. This was a dark time for poor zero.

Zero may have little meaning in ancient Europe, but that did not mean that people in other parts of the world weren’t interested in what it could offer. In India, scholars were developing symbols for numbers that were easier to use, including one that stood in for zero—an oval with a dot in the middle. Over time, this symbol, which was also used as placeholder at first, not only lost the dot, but also became a number in its own right. By the 600s CE, “0” had begun a new chapter.

From Zero to Hero

From Zero to Hero

So far, we have only seen zero as a mere placeholder, not as a number in its own right. All that changed when a seventh-century Indian astronomer named Brahmagupta wrote a book that defined the rules for arithmetic operations using zero and negative numbers. Zero became a boundary between positive and negative numbers, which revolutionized math. Now, zero could do more than just stand in place; it could be added and subtracted as well as multiplied and divided. Eventually, it would serve as an exponent as well as play a role in other more complex operations.

Brahmagupta’s work was studied throughout the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East. At the turn of the 800s, al-Khwarizmi, a Persian mathematician and scholar, particularly embraced this concept of 0 and included it in a new number system denoted with the numerals 0 through 9. His work popularized the Hindu-Arabic numbers that we know and love today. Al-Khwarizmi also explored the possibilities of zero as a number, laying the foundation for algebra.

Brahmagupta’s work was studied throughout the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East. At the turn of the 800s, al-Khwarizmi, a Persian mathematician and scholar, particularly embraced this concept of 0 and included it in a new number system denoted with the numerals 0 through 9. His work popularized the Hindu-Arabic numbers that we know and love today. Al-Khwarizmi also explored the possibilities of zero as a number, laying the foundation for algebra.

A Florentine scholar and merchant, Fibonacci, brought this number system to Italy and Europe. Although mistrusted at first because of their origin, Hindu-Arabic numerals were easier to use than Roman numerals and more Europeans began to use them for everything from accounting to the development algebra. This had the effect of democratizing math in Europe especially. Now, average people could understand and work with larger numbers without needing specialized teachers. Zero was an important part of spreading math literacy.

A Florentine scholar and merchant, Fibonacci, brought this number system to Italy and Europe. Although mistrusted at first because of their origin, Hindu-Arabic numerals were easier to use than Roman numerals and more Europeans began to use them for everything from accounting to the development algebra. This had the effect of democratizing math in Europe especially. Now, average people could understand and work with larger numbers without needing specialized teachers. Zero was an important part of spreading math literacy.

Are you looking for more math challenges? Check out A Grade Ahead’s upper-level math enrichment classes.

European mathematicians particularly loved the concept of zero and what it could help us do. Around the turn of the 1700s, Gottfried Leibniz particularly used it to build on Chinese and Indian concepts of binary systems. The ancient Chinese work, I Ching or Yijing, had introduced the concept of yin and yang, and Pingala, an Indian philosopher, had used a binary system to contemplate linguistics. Liebniz, though, conceived of a binary number system using 1s and 0s. He not only believed that such a system represented divine creation, but he also thought that it would simplify complex mathematical operations. This is why binary code became essential to the development of computers, which rely on the 1s and 0s to function. So, zero was proving itself.

European mathematicians particularly loved the concept of zero and what it could help us do. Around the turn of the 1700s, Gottfried Leibniz particularly used it to build on Chinese and Indian concepts of binary systems. The ancient Chinese work, I Ching or Yijing, had introduced the concept of yin and yang, and Pingala, an Indian philosopher, had used a binary system to contemplate linguistics. Liebniz, though, conceived of a binary number system using 1s and 0s. He not only believed that such a system represented divine creation, but he also thought that it would simplify complex mathematical operations. This is why binary code became essential to the development of computers, which rely on the 1s and 0s to function. So, zero was proving itself.

Liebniz and Sir Isaac Newton also valued the properties of zero when they began to define the rules of calculus, which physicists and engineers use to explore the boundaries of science and discover its infinite possibilities.

Liebniz and Sir Isaac Newton also valued the properties of zero when they began to define the rules of calculus, which physicists and engineers use to explore the boundaries of science and discover its infinite possibilities.

So, zero became a hero in math.

Zero’s Adventures Today

Today, zero is so much more than a placeholder. Scholars in diverse fields depend on the properties of zero to conduct their research. Everyone from economists to physicists rely on zero because it does not just represent the absence of something but also represents the boundary between something and less than something. For example, in thermodynamics, 0º Kelvin represents the lowest possible temperature and the point at which an object has absolutely no heat energy to exchange. Rocket scientists use it to calculate trajectories. Economists and business leaders see zero as the boundary between profit and loss and use it to study trends. And all of us rely on zeros every time we use a computer.

So, the discovery of zero is even more amazing than the invention of sliced bread.

How do you use zero? Add your story in the comments below!

Author: Susanna Robbins, Teacher and Franchise Assistant at A Grade Ahead